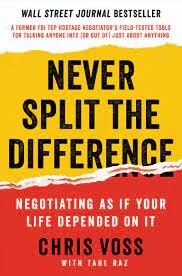

Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It

Chris Voss and Tahl Raz

“I’m sorry, Robert, how do I know he’s even alive?” I said, using an apology and his first name, seeding more warmth into the interaction in order to complicate his gambit to bulldoze me. “I really am sorry, but how can I get you any money right now, much less one million dollars, if I don’t even know he’s alive?”

Location: 238

I was employing what had become one of the FBI’s most potent negotiating tools: the open-ended question.

Location: 242

The Black Swan Group, we call this tactic calibrated questions: queries that the other side can respond to but that have no fixed answers. It buys you time. It gives your counterpart the illusion of control—they are the one with the answers and power after all—and it does all that without giving them any idea of how constrained they are by it.

Location: 244

the frame of the conversation had shifted from how I’d respond to the threat of my son’s murder to how the professor would deal with the logistical issues involved in getting the money.

Location: 246

How he would solve my problems. To

Location: 248

Andy would throw out an offer and give a rationally airtight explanation for why it was a good one—an inescapable logic trap—and I’d answer with some variation of “How am I supposed to do that?”

Location: 280

While I wasn’t actually saying “No,” the questions I kept asking sounded like it. They seemed to insinuate that the other side was being dishonest and unfair. And that was enough to make them falter and negotiate with themselves.

Location: 300

“I’m just asking questions,” I said. “It’s a passive-aggressive approach. I just ask the same three or four open-ended questions over and over and over and over. They get worn out answering and give me everything I want.”

Location: 303

authoritative acronyms like BATNA and ZOPA, rational notions of value, and a moral concept of what was fair and what was not. And

Location: 315

Getting to Yes,2 a groundbreaking treatise on negotiation that totally

Location: 353

Their core assumption was that the emotional brain—that animalistic, unreliable, and irrational beast—could be overcome through a more rational, joint problem-solving mindset.

Location: 355

One, separate the person—the emotion—from the problem; two, don’t get wrapped up in the other side’s position (what they’re asking for) but instead focus on their interests (why they’re asking for it) so that you can find what they really want; three, work cooperatively to generate win-win options; and, four, establish mutually agreed-upon standards for evaluating those possible solutions.

Location: 357

the Framing Effect, which demonstrates that people respond differently to the same choice depending on how it is framed (people place greater value on moving from 90 percent to 100 percent—high probability to certainty—than from 45 percent to 55 percent, even though they’re both ten percentage points).

Location: 374

Loss Aversion, which shows how people are statistically more likely to act to avert a loss than to achieve an equal gain. Kahneman later codified his research in the 2011 bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow.3 Man, he wrote, has two systems of thought: System 1, our animal mind, is fast, instinctive, and emotional; System 2 is slow, deliberative, and logical. And System 1 is far more influential. In fact, it guides and steers our rational thoughts. System 1’s inchoate beliefs, feelings, and impressions are the main sources of the explicit beliefs and deliberate choices of System 2. They’re the spring that feeds the river. We react emotionally (System 1) to a suggestion or question. Then that System 1 reaction informs and in effect creates the System 2 answer.

Location: 377

From that moment onward, our emphasis would have to be not on training in quid pro quo bargaining and problem solving, but on education in the psychological skills needed in crisis intervention situations. Emotions and emotional intelligence would have to be central to effective negotiation, not things to be overcome. What were needed were simple psychological tactics and strategies that worked in the field to calm people down, establish rapport, gain trust, elicit the verbalization of needs, and persuade the other guy of our empathy. We needed something easy to teach, easy to learn, and easy to execute.

Location: 417

It all starts with the universally applicable premise that people want to be understood and accepted. Listening is the cheapest, yet most effective concession we can make to get there. By listening intensely, a negotiator demonstrates empathy and shows a sincere desire to better understand what the other side is experiencing.

Location: 427

Psychotherapy research shows that when individuals feel listened to, they tend to listen to themselves more carefully and to openly evaluate and clarify their own thoughts and feelings. In addition, they tend to become less defensive and oppositional and more willing to listen to other points of view, which gets them to the calm and logical place where they can be good Getting to Yes problem solvers.

Location: 429

Tactical Empathy. This is listening as a martial art, balancing the subtle behaviors of emotional intelligence and the assertive skills of influence, to gain access to the mind of another person. Contrary to popular opinion, listening is not a passive activity. It is the most active thing you can do.

Location: 433

Negotiation serves two distinct, vital life functions—information gathering and behavior influencing—and includes almost any interaction where each party wants something from the other side. Your career, your finances, your reputation, your love life, even the fate of your kids—at some point all of these hinge on your ability to negotiate.

Location: 447

Effective negotiation is applied people smarts, a psychological edge in every domain of life: how to size someone up, how to influence their sizing up of you, and how to use that knowledge to get what you want. But beware: this is not

Location: 463

No. A successful hostage negotiator has to get everything he asks for, without giving anything back of substance, and do so in a way that leaves the adversaries feeling as if they have a great relationship.

Location: 471

Great negotiators are able to question the assumptions that the rest of the involved players accept on faith or in arrogance, and thus remain more emotionally open to all possibilities, and more intellectually agile to a fluid situation.

Location: 557

I hadn’t yet learned to be aware of a counterpart’s overuse of personal pronouns—we/they or me/I. The less important he makes himself, the more important he probably is (and vice versa).

Location: 562

We are easily distracted. We engage in selective listening, hearing only what we want to hear, our minds acting on a cognitive bias for consistency rather than truth. And that’s just the start. Most people approach a negotiation so preoccupied by the arguments that support their position that they are unable to listen attentively. In one of the most cited research papers in psychology,1 George A. Miller persuasively put forth the idea that we can process only about seven pieces of information in our conscious mind at any given moment. In other words, we are easily overwhelmed.

Location: 591

Instead of prioritizing your argument—in fact, instead of doing any thinking at all in the early goings about what you’re going to say—make your sole and all-encompassing focus the other person and what they have to say. In that mode of true active listening—aided by the tactics you’ll learn in the following chapters—you’ll disarm your counterpart. You’ll make them feel safe.

Location: 602

The goal is to identify what your counterparts actually need (monetarily, emotionally, or otherwise) and get them feeling safe enough to talk and talk and talk some more about what they want.

Location: 605

Going too fast is one of the mistakes all negotiators are prone to making. If we’re too much in a hurry, people can feel as if they’re not being heard and we risk undermining the rapport and trust we’ve built. There’s plenty of research that now validates the passage of time as one of the most important tools for a negotiator. When you slow the process down, you also calm it down.

Location: 631

I didn’t put it like a question. I made a downward-inflecting statement, in a downward-inflecting tone of voice. The best way to describe the late-night FM DJ’s voice is as the voice of calm and reason. When deliberating on a negotiating strategy or approach, people tend to focus all their energies on what to say or do, but it’s how we are (our general demeanor and delivery) that is both the easiest thing to enact and the most immediately effective mode of influence.

Location: 655

When we radiate warmth and acceptance, conversations just seem to flow. When we enter a room with a level of comfort and enthusiasm, we attract people toward us. Smile at someone on the street, and as a reflex they’ll smile back. Understanding that reflex and putting it into practice is critical to the success of just about every negotiating skill there is to learn.

Location: 663

When people are in a positive frame of mind, they think more quickly, and are more likely to collaborate and problem-solve (instead of fight and resist). It applies to the smile-er as much as to the smile-ee: a smile on your face, and in your voice, will increase your own mental agility.

Location: 680

You can be very direct and to the point as long as you create safety by a tone of voice that says I’m okay, you’re okay, let’s figure things out.

Location: 690

Mirroring, also called isopraxism, is essentially imitation. It’s another neurobehavior humans (and other animals) display in which we copy each other to comfort each other. It can be done with speech patterns, body language, vocabulary, tempo, and tone of voice. It’s generally an unconscious behavior—we are rarely aware of it when it’s happening—but it’s a sign that people are bonding, in sync, and establishing the kind of rapport that leads to trust. It’s a phenomenon (and now technique) that follows a very basic but profound biological principle: We fear what’s different and are drawn to what’s similar.

Location: 710

It’s almost laughably simple: for the FBI, a “mirror” is when you repeat the last three words (or the critical one to three words) of what someone has just said. Of the entirety of the FBI’s hostage negotiation skill set, mirroring is the closest one gets to a Jedi mind trick. Simple, and yet uncannily effective. By

Location: 721

The results were stunning: the average tip of the waiters who mirrored was 70 percent more than of those who used positive reinforcement.

Location: 728

If you take a pit bull approach with another pit bull, you generally end up with a messy scene and lots of bruised feelings and resentment. Luckily, there’s another way without all the mess. It’s just four simple steps: 1. Use the late-night FM DJ voice. 2. Start with “I’m sorry . . .” 3. Mirror. 4. Silence. At least four seconds, to let the mirror work its magic on your counterpart. 5. Repeat.

Location: 840

“I’m sorry, two copies?” she mirrored in response, remembering not only the DJ voice, but to deliver the mirror in an inquisitive tone. The intention behind most mirrors should be “Please, help me understand.” Every time you mirror someone, they will reword what they’ve said. They will never say it exactly the same way they said it the first time. Ask someone, “What do you mean by that?” and you’re likely to incite irritation or defensiveness. A mirror, however, will get you the clarity you want while signaling respect and concern for what the other person is saying. “Yes,” her boss responded, “one for us and one for the customer.” “I’m sorry, so you are saying that the client is asking for a copy and we need a copy for internal use?” “Actually, I’ll check with the client—they haven’t asked for anything. But I definitely want a copy. That’s just how I do business.” “Absolutely,” she responded. “Thanks for checking with the customer. Where would you like to store the in-house copy? There’s no more space in the file room here.” “It’s fine. You can store it anywhere,” he said, slightly perturbed now. “Anywhere?” she mirrored again, with calm concern. When another person’s tone of voice or body language is inconsistent with his words, a good mirror can be particularly useful. In this case, it caused her boss to take a nice, long pause—something he did not often do. My student sat silent. “As a matter of fact, you can put them in my office,” he said, with more composure than he’d had the whole conversation. “I’ll get the new assistant to print it for me after the project is done. For now, just create two digital backups.” A day later her boss emailed and wrote simply, “The two digital backups will be fine.”

Location: 854

The language of negotiation is primarily a language of conversation and rapport: a way of quickly establishing relationships and getting people to talk and think together.

Location: 873

good negotiator prepares, going in, to be ready for possible surprises; a great negotiator aims to use her skills to reveal the surprises she is certain to find. ■ Don’t commit to assumptions; instead, view them as hypotheses and use the negotiation to test them rigorously.

Location: 883

People who view negotiation as a battle of arguments become overwhelmed by the voices in their head. Negotiation is not an act of battle; it’s a process of discovery. The goal is to uncover as much information as possible. ■ To quiet the voices in your head, make your sole and all-encompassing focus the other person and what they have to say. ■ Slow. It. Down. Going too fast is one of the mistakes all negotiators are prone to making. If we’re too much in a hurry, people can feel as if they’re not being heard. You risk undermining the rapport and trust you’ve built.

Location: 887

■ Put a smile on your face. When people are in a positive frame of mind, they think more quickly, and are more likely to collaborate and problem-solve (instead of fight and resist). Positivity creates mental agility in both you and your counterpart.

Location: 893

But think about that: How can you separate people from the problem when their emotions are the problem?

Location: 916

Emotions are one of the main things that derail communication. Once people get upset at one another, rational thinking goes out the window. That’s why, instead of denying or ignoring emotions, good negotiators identify and influence them.

Location: 917

You can learn almost everything you need—and a lot more than other people would like you to know—simply by watching and listening, keeping your eyes peeled and your ears open, and your mouth shut.

Location: 925

Think about the therapist’s couch as you read the following sections. You’ll see how a soothing voice, close listening, and a calm repetition of the words of your “patient” can get you a lot further than a cold, rational argument.

Location: 927

Instead, I imagined myself in their place. “It looks like you don’t want to come out,” I said repeatedly. “It seems like you worry that if you open the door, we’ll come in with guns blazing. It looks like you don’t want to go back to jail.”

Location: 934

In my negotiating course, I tell my students that empathy is “the ability to recognize the perspective of a counterpart, and the vocalization of that recognition.” That’s an academic way of saying that empathy is paying attention to another human being, asking what they are feeling, and making a commitment to understanding their world.

Location: 946

Most of us enter verbal combat unlikely to persuade anyone of anything because we only know and care about our own goals and perspective.

Location: 958

We didn’t just put ourselves in the fugitives’ shoes. We spotted their feelings, turned them into words, and then very calmly and respectfully repeated their emotions back to them. In a negotiation, that’s called labeling. Labeling is a way of validating someone’s emotion by acknowledging it. Give someone’s emotion a name and you show you identify with how that person feels.

Location: 989

Think of labeling as a shortcut to intimacy, a time-saving emotional hack.

Location: 993

For most people, it’s one of the most awkward negotiating tools to use. Before they try it the first time, my students almost always tell me they expect their counterpart to jump up and shout, “Don’t you dare tell me how I feel!” Let me let you in on a secret: people never even notice.

Location: 1001

Once you’ve spotted an emotion you want to highlight, the next step is to label it aloud. Labels can be phrased as statements or questions. The only difference is whether you end the sentence with a downward or upward inflection. But no matter how they end, labels almost always begin with roughly the same words: It seems like . . . It sounds like . . . It looks like . . . Notice we said “It sounds like . . .” and not “I’m hearing that . . .” That’s because the word “I” gets people’s guard up. When you say “I,” it says you’re more interested in yourself than the other person, and it makes you take personal responsibility for the words that follow—and the offense they might cause. But when you phrase a label as a neutral statement of understanding, it encourages your counterpart to be responsive.

Location: 1014

The last rule of labeling is silence. Once you’ve thrown out a label, be quiet and listen. We all have a tendency to expand on what we’ve said, to finish, “It seems like you like the way that shirt looks,” with a specific question like “Where did you get it?” But a label’s power is that it invites the other person to reveal himself.

Location: 1023

Imagine a grandfather who’s grumbly at a family holiday dinner: the presenting behavior is that he’s cranky, but the underlying emotion is a sad sense of loneliness from his family never seeing him. What good negotiators do when labeling is address those underlying emotions. Labeling negatives diffuses them (or defuses them, in extreme cases); labeling positives reinforces them.

Location: 1033

As an emotion, anger is rarely productive—in you or the person you’re negotiating with. It releases stress hormones and neurochemicals that disrupt your ability to properly evaluate and respond to situations. And it blinds you to the fact that you’re angry in the first place, which gives you a false sense of confidence. That’s not to say that negative feelings should be ignored. That can be just as damaging. Instead, they should be teased out. Labeling is a helpful tactic in de-escalating angry confrontations, because it makes the person acknowledge their feelings rather than continuing to act out.

Location: 1037

Try this the next time you have to apologize for a bone-headed mistake. Go right at it. The fastest and most efficient means of establishing a quick working relationship is to acknowledge the negative and diffuse it. Whenever

Location: 1054

And when I make a mistake—something that happens a lot—I always acknowledge the other person’s anger. I’ve found the phrase “Look, I’m an asshole” to be an amazingly effective way to make problems go away.

Location: 1056

Research shows that the best way to deal with negativity is to observe it, without reaction and without judgment. Then consciously label each negative feeling and replace it with positive, compassionate, and solution-based thoughts. One

Location: 1066

“I wanted to inform you,” it read, “that in order to receive your tickets for the upcoming season opener against the New York Giants, you will need to pay your outstanding balance in full prior to September 10.” It was the stupidly aggressive, impersonal, tone-deaf style of communication that is the default for most business. It was all “me, me, me” from TJ, with no acknowledgment of the ticket holder’s situation. No empathy. No connection. Just give me the money. Maybe I don’t need to say it, but the script didn’t work. TJ left messages; no one called back.

Location: 1077

the faster we can interrupt the amygdala’s reaction to real or imaginary threats, the faster we can clear the road of obstacles, and the quicker we can generate feelings of safety, well-being, and trust. We do that by labeling the fears. These labels are so powerful because they bathe the fears in sunlight, bleaching them of their power and showing our counterpart that we understand.

Location: 1093

By digging beneath what seems like a mountain of quibbles, details, and logistics, labels help to uncover and identify the primary emotion driving almost all of your counterpart’s behavior, the emotion that, once acknowledged, seems to miraculously solve everything else. DO AN ACCUSATION AUDIT On

Location: 1125

I always end up with more volunteers than I need. Now, look at what I did: I prefaced the conversation by labeling my audience’s fears; how much worse can something be than “horrible”? I defuse them and wait, letting it sink in and thereby making the unreasonable seem less forbidding.

Location: 1137

The first step of doing so is listing every terrible thing your counterpart could say about you, in what I call an accusation audit.

Location: 1146

Anna opened by acknowledging ABC’s biggest gripes. “We understand that we brought you on board with the shared goal of having you lead this work,” she said. “You may feel like we have treated you unfairly, and that we changed the deal significantly since then. We acknowledge that you believe you were promised this work.”

Location: 1176

“What else is there you feel is important to add to this?” By labeling the fears and asking for input, Anna was able to elicit an important fact about ABC’s fears, namely that ABC was expecting this to be a high-profit contract because it thought Anna’s firm was doing quite well from the deal.

Location: 1180

Watch what they do closely, as it’s brilliant: they acknowledge ABC’s situation while simultaneously shifting the onus of offering a solution to the smaller company. “It sounds like you have a great handle on how the government contract should work,” Anna said, labeling Angela’s expertise. “Yes—but I know that’s not how it always goes,” Angela answered, proud to have her experience acknowledged. Anna then asked Angela how she would amend the contract so that everyone made some money, which pushed Angela to admit that she saw no way to do so without cutting ABC’s worker count.

Location: 1187

To start, watch how Ryan turns that heated exchange to his advantage. Following on the heels of an argument is a great position for a negotiator, because your counterpart is desperate for an empathetic connection. Smile, and you’re already an improvement. “Hi, Wendy, I’m Ryan. It seems like they were pretty upset.” This labels the negative and establishes a rapport based on empathy. This in turn encourages Wendy to elaborate on her situation, words Ryan then mirrors to invite her to go further. “Yeah. They missed their connection. We’ve had a fair amount of delays because of the weather.”

Location: 1219

After Wendy explains how the delays in the Northeast had rippled through the system, Ryan again labels the negative and then mirrors her answer to encourage her to delve further. “It seems like it’s been a hectic day.” “There’ve been a lot of ‘irate consumers,’ you know? I mean, I get it, even though I don’t like to be yelled at. A lot of people are trying to get to Austin for the big game.” “The big game?” “UT is playing Ole Miss football and every flight into Austin has been booked solid.” “Booked solid?” Now let’s pause. Up to this point, Ryan has been using labels and mirrors to build a relationship with Wendy. To her it must seem like idle chatter, though, because he hasn’t asked for anything. Unlike the angry couple, Ryan is acknowledging her situation. His words ping-pong between “What’s that?” and “I hear you,” both of which invite her to elaborate. Now that the empathy has been built, she lets slip a piece of information he can use. “Yeah, all through the weekend.

Location: 1224

Here’s where Ryan finally swoops in with an ask. But notice how he acts: not assertive or coldly logical, but with empathy and labeling that acknowledges her situation and tacitly puts them in the same boat. “Well, it seems like you’ve been handling the rough day pretty well,” he says. “I was also affected by the weather delays and missed my connecting flight. It seems like this flight is likely booked solid, but with what you said, maybe someone affected by the weather might miss this connection. Is there any possibility a seat will be open?” Listen to that riff: Label, tactical empathy, label. And only then a request.

Location: 1235

As you try to insert the tools of tactical empathy into your daily life, I encourage you to think of them as extensions of natural human interactions and not artificial conversational tics.

Location: 1246

Imagine yourself in your counterpart’s situation. The beauty of empathy is that it doesn’t demand that you agree with the other person’s ideas (you may well find them crazy). But by acknowledging the other person’s situation, you immediately convey that you are listening. And once they know that you are listening, they may tell you something that you can use. ■ The reasons why a counterpart will not make an agreement with you are often more powerful than why they will make a deal, so focus first on clearing the barriers to agreement. Denying barriers or negative influences gives them credence; get them into the open.

Location: 1257

Pause. After you label a barrier or mirror a statement, let it sink in. Don’t worry, the other party will fill the silence. ■ Label your counterpart’s fears to diffuse their power. We all want to talk about the happy stuff, but remember, the faster you interrupt action in your counterpart’s amygdala, the part of the brain that generates fear, the faster you can generate feelings of safety, well-being, and trust. ■ List the worst things that the other party could say about you and say them before the other person can. Performing an accusation audit in advance prepares you to head off negative dynamics before they take root. And because these accusations often sound exaggerated when said aloud, speaking them will encourage the other person to claim that quite the opposite is true. ■ Remember you’re dealing with a person who wants to be appreciated and understood. So use labels to reinforce and encourage positive perceptions and dynamics.

Location: 1263

“Yes” and “Maybe” are often worthless. But “No” always alters the conversation.

Location: 1297

all related to negotiation?” “No.” “Looks like you answered your own question,” she said. “No. Now go away.” “Go away?” I protested. “Really?” “Yep. As in, ‘Leave me alone.’ Everybody wants to be a hostage negotiator, and you have no résumé, experience, or skills. So what would you say in my position? You got it: ‘No.’” I paused in front of her, thinking, This is not how my negotiating career ends. I had stared down terrorists; I wasn’t going to just leave. “Come on,” I said. “There has to be something I can do.” Amy shook her head and gave one of those ironic laughs that mean the person doesn’t think you’ve got a snowball’s chance in hell. “I’ll tell you what. Yes, there is something you can do: Volunteer at a suicide hotline. Then come talk to me. No guarantees, got it?” she said. “Now, seriously, go away.”

Location: 1314

started to see that while people played the game of conversation, it was in the game beneath the game, where few played, that all the leverage lived. In our chat, I saw how the word “No”—so apparently clear and direct—really wasn’t so simple. Over the years, I’ve thought back repeatedly to that conversation, replaying how Amy so quickly turned me down, again and again. But her “No’s” were just the gateway to “Yes.” They gave her—and me—time to pivot, adjust, and reexamine, and actually created the environment for the one “Yes” that mattered.

Location: 1325

At first, I thought that sort of automated response signaled a failure of imagination. But then I realized I did the same thing with my teenage son, and that after I’d said “No” to him, I often found that I was open to hearing what he had to say. That’s because having protected myself, I could relax and more easily…

Location: 1332

Jim Camp, in his excellent book, Start with NO,1 counsels the reader to give their adversary (his word for counterpart) permission to say “No” from the outset of a negotiation. He calls it “the right to veto.” He observes that people will fight to the death to preserve their right to say “No,” so give them that right and the…

Location: 1338

When I read Camp’s book, I realized this was something we’d known as hostage negotiators for years. We’d learned that the quickest way to get a hostage-taker out was to take the time to talk them out, as opposed to “demanding” their surrender. Demanding their surrender, “telling” them to come out, always ended up…

Location: 1342

It comes down to the deep and universal human need for autonomy. People need to feel in control. When you preserve a person’s autonomy by clearly giving them permission to say “No” to your ideas, the emotions calm, the effectiveness of the decisions go up, and the other party can really look at your proposal. They’re allowed to hold it in their hands, to turn it around. And it gives you time to elaborate or pivot in order to convince your counterpart that the change you’re proposing is more…

Location: 1345

Politely saying “No” to your opponent (we’ll go into this in more depth in Chapter 9), calmly hearing “No,” and just letting the other side know that they are welcome to say “No” has a positive impact on any negotiation. In fact, your invitation for the other side to say “No” has an…

Location: 1350

Then, after pausing, ask solution-based questions or simply label their effect: “What about this doesn’t work for you?” “What would you need to make it work?” “It seems like there’s something here that bothers you.” People have a need to say, “No.” So don’t just hope to hear it at some point; get them to say it early.

Location: 1362

His negotiation style is all me, me, me, ego, ego, ego. And when the people on the other side of the table pick up those signals, they’re going to decide that it’s best to politely, even furtively, ignore this Superman . . . by saying “Yes”! “Huh?” you say. Sure, the word they’ll say right off is “Yes,” but that word is only a tool to get this blowhard to go away. They’ll weasel out later, claiming changing conditions, budget issues, the weather. For now, they just want to be released because Joe isn’t convincing them of anything; he’s only convincing himself. I’ll let you in on a secret. There are actually three kinds of “Yes”: Counterfeit, Confirmation, and Commitment. A counterfeit “yes” is one in which your counterpart plans on saying “no” but either feels “yes” is an easier escape route or just wants to disingenuously keep the conversation going to obtain more information or some other kind of edge. A confirmation “yes” is generally innocent, a reflexive response to a black-or-white question; it’s sometimes used to lay a trap but mostly it’s just simple affirmation with no promise of action. And a commitment “yes” is the real deal; it’s a true agreement that leads to action, a “yes” at the table that ends with a signature on the contract. The commitment “yes” is what you want, but the three types sound almost the same so you have to learn how to recognize which one is being used.

Location: 1371

the only way to get these callers to take action was to have them own the conversation, to believe that they were coming to these conclusions, to these necessary next steps, and that the voice at the other end was simply a medium for those realizations. Using all your skills to create rapport, agreement, and connection with a counterpart is useful, but ultimately that connection is useless unless the other person feels that they are equally as responsible, if not solely responsible, for creating the connection and the new ideas they have.

Location: 1424

Got it, you say. It’s not about me. We need to persuade from their perspective, not ours. But how? By starting with their most basic wants. In every negotiation, in every agreement, the result comes from someone else’s decision. And sadly, if we believe that we can control or manage others’ decisions with compromise and logic, we’re leaving millions on the table. But while we can’t control others’ decisions, we can influence them by inhabiting their world and seeing and hearing exactly what they want. Though the intensity may differ from person to person, you can be sure that everyone you meet is driven by two primal urges: the need to feel safe and secure, and the need to feel in control. If you satisfy those drives, you’re in the door. As we saw with my chat with Daryl, you’re not going to logically

Location: 1431

convince them that they’re safe, secure, or in control. Primal needs are urgent and illogical, so arguing them into a corner is just going to push your counterpart to flee with a counterfeit “Yes.”

Location: 1438

Good negotiators welcome—even invite—a solid “No” to start, as a sign that the other party is engaged and thinking.

Location: 1462

That’s why I tell my students that, if you’re trying to sell something, don’t start with “Do you have a few minutes to talk?” Instead ask, “Is now a bad time to talk?” Either you get “Yes, it is a bad time” followed by a good time or a request to go away, or you get “No, it’s not” and total focus.

Location: 1464

by the time she sat down with him, she had picked one of the most strongly worded “No”-oriented setup questions I have ever heard. “Do you want the FBI to be embarrassed?” she said. “No,” he answered. “What do you want me to do?” she responded. He leaned back in his chair, one of those 1950s faux-leather numbers that squeak meaningfully when the sitter shifts. He stared at her over his glasses and then nodded ever so slightly. He was in control. “Look, you can keep the position,” he said. “Just go back out there and don’t let it interfere with your other duties.” And a minute later Marti walked out with her job intact.

Location: 1478

When I heard Marti do that, I was like, “Bang!” By pushing for a “No,” Marti nudged her supervisor into a zone where he was making the decisions. And then she furthered his feelings of safety and power with a question inviting him to define her next move. The important thing here is that Marti not only accepted the “No”; she searched it out and embraced it. At a recent sales conference, I asked the participants for the one word they all dread. The entire group yelled, “No!” To them—and to almost everyone—“No” means one thing: end of discussion. But that’s not what it means. “No” is not failure. Used strategically it’s an answer that opens the path forward.

Location: 1484

Getting to the point where you’re no longer horrified by the word “No” is a liberating moment that every negotiator needs to reach. Because if your biggest fear is “No,” you can’t negotiate. You’re the hostage of “Yes.” You’re handcuffed. You’re done. So

Location: 1490

As you can see, “No” has a lot of skills. ■ “No” allows the real issues to be brought forth; ■ “No” protects people from making—and lets them correct—ineffective decisions; ■ “No” slows things down so that people can freely embrace their decisions and the agreements they enter into; ■ “No” helps people feel safe, secure, emotionally comfortable, and in control of their decisions; ■ “No” moves everyone’s efforts forward.

Location: 1502

The problem, in reality, was that the “Yes pattern” scripts had been giving poor rates of return for years. All the steps were “Yes,” but the final answer was invariably “No.” Then Ben read Jim Camp’s book Start with NO in my class and began to wonder if “No” could be a tool to boost donations.

Location: 1524

Sometimes, if you’re talking to somebody who is just not listening, the only way you can crack their cranium is to antagonize them into “No.” One great way to do this is to mislabel one of the other party’s emotions or desires. You say something that you know is totally wrong, like “So it seems that you really are eager to leave your job” when they clearly want to stay. That forces them to listen and makes them comfortable correcting you by saying, “No, that’s not it. This is it.”

Location: 1546

you send a polite follow-up and they stonewall you again. So what do you do? You provoke a “No” with this one-sentence email. Have you given up on this project? The point is that this one-sentence email encapsulates the best of “No”-oriented questions and plays on your counterpart’s natural human aversion to loss. The “No” answer the email demands offers the other party the feeling of safety and the illusion of control while encouraging them to define their position and explain it to you.

Location: 1559

We’ve instrumentalized niceness as a way of greasing the social wheels, yet it’s often a ruse. We’re polite and we don’t disagree to get through daily existence with the least degree of friction. But by turning niceness into a lubricant, we’ve leeched it of meaning. A smile and a nod might signify “Get me out of here!” as much as it means “Nice to meet you.” That’s death for a good negotiator, who gains their power by understanding their counterpart’s situation and extracting information about their counterpart’s desires and needs. Extracting that information means getting the other party to feel safe and in control. And while it may sound contradictory, the way to get there is by getting the other party to disagree, to draw their own boundaries, to define their desires as a function of what they do not want.

Location: 1574

■ Break the habit of attempting to get people to say “yes.” Being pushed for “yes” makes people defensive. Our love of hearing “yes” makes us blind to the defensiveness we ourselves feel when someone is pushing us to say it. ■ “No” is not a failure. We have learned that “No” is the anti-“Yes” and therefore a word to be avoided at all costs. But it really often just means “Wait” or “I’m not comfortable with that.” Learn how to hear it calmly. It is not the end of the negotiation, but the beginning. ■ “Yes” is the final goal of a negotiation, but don’t aim for it at the start. Asking someone for “Yes” too quickly in a conversation—“Do you like to drink water, Mr. Smith?”—gets his guard up and paints you as an untrustworthy salesman. ■ Saying “No” makes the speaker feel safe, secure, and in control, so trigger it. By saying what they don’t want, your counterpart defines their space and gains the confidence and comfort to listen to you. That’s why “Is now a bad time to talk?” is always better than “Do you have a few minutes to talk?” ■ Sometimes the only way to get your counterpart to listen and engage with you is by forcing them into a “No.” That means intentionally mislabeling one of their emotions or desires or asking a ridiculous question—like, “It seems like you want this project to fail”—that can only be answered negatively. ■ Negotiate in their world. Persuasion is not about how bright or smooth or forceful you are. It’s about the other party convincing themselves that the solution you want is their own idea. So don’t beat

Location: 1584

them with logic or brute force. Ask them questions that open paths to your goals. It’s not about you. ■ If a potential business partner is ignoring you, contact them with a clear and concise “No”-oriented question that suggests that you are ready to walk away. “Have you given up on this project?” works wonders.

Location: 1599

CNU developed what is a powerful staple in the high-stakes world of crisis negotiation, the Behavioral Change Stairway Model (BCSM). The model proposes five stages—active listening, empathy, rapport, influence, and behavioral change—that take any negotiator from listening to influencing behavior.

Location: 1615

Before you convince them to see what you’re trying to accomplish, you have to say the things to them that will get them to say, “That’s right.” The “that’s right” breakthrough usually doesn’t come at the beginning of a negotiation. It’s invisible to the counterpart when it occurs, and they embrace what you’ve said. To them, it’s a subtle epiphany.

Location: 1691

page document that instructed Benjie to change course. We were going to use nearly every tactic in the active listening arsenal: 1. Effective Pauses: Silence is powerful. We told Benjie to use it for emphasis, to encourage Sabaya to keep talking until eventually, like clearing out a swamp, the emotions were drained from the dialogue. 2. Minimal Encouragers: Besides silence, we instructed using simple phrases, such as “Yes,” “OK,” “Uh-huh,” or “I see,” to effectively convey that Benjie was now paying full attention to Sabaya and all he had to say. 3. Mirroring: Rather than argue with Sabaya and try to separate Schilling from the “war damages,” Benjie would listen and repeat back what Sabaya said. 4. Labeling: Benjie should give Sabaya’s feelings a name and identify with how he felt. “It all seems so tragically unfair, I can now see why you sound so angry.” 5. Paraphrase: Benjie should repeat what Sabaya is saying back to him in Benjie’s own words. This, we told him, would powerfully show him you really do understand and aren’t merely parroting his concerns. 6. Summarize: A good summary is the combination of rearticulating the meaning of what is said plus the acknowledgment of the emotions underlying that meaning (paraphrasing + labeling = summary). We told Benjie he needed to listen and repeat the “world according to Abu Sabaya.” He needed to fully and completely summarize all the nonsense that Sabaya had come up with about war damages and fishing rights and five hundred years of oppression. And once he did that fully and completely, the only possible response for Sabaya, and anyone faced with a good summary, would be “that’s right.”

Location: 1702

It works every time. Tell people “you’re right” and they get a happy smile on their face and leave you alone for at least twenty-four hours. But you haven’t agreed to their position. You have used “you’re right” to get them to quit bothering you.

Location: 1757

The power of getting to that understanding, and not to some simple “yes,” is revelatory in the art of negotiation. The moment you’ve convinced someone that you truly understand her dreams and feelings (the whole world that she inhabits), mental and behavioral change becomes possible, and the foundation for a breakthrough has been laid.

Location: 1841

Use these lessons to lay that foundation: ■ Creating unconditional positive regard opens the door to changing thoughts and behaviors. Humans have an innate urge toward socially constructive behavior. The more a person feels understood, and positively affirmed in that understanding, the more likely that urge for constructive behavior will take hold. ■ “That’s right” is better than “yes.” Strive for it. Reaching “that’s right” in a negotiation creates breakthroughs. ■ Use a summary to trigger a “that’s right.” The building blocks of a good summary are a label combined with paraphrasing. Identify, rearticulate, and emotionally affirm “the world according to . .

Location: 1843

when you get a call from brutal criminals who say they’ll kill your aunt unless you pay them immediately, it seems impossible to find leverage in the situation. So you pay the ransom and they release your relative, right? Wrong. There’s always leverage. Negotiation is never a linear formula: add X to Y to get Z. We all have irrational blind spots, hidden needs, and undeveloped notions.

Location: 1871

Once you understand that subterranean world of unspoken needs and thoughts, you’ll discover a universe of variables that can be leveraged to change your counterpart’s needs and expectations. From using some people’s fear of deadlines and the mysterious power of odd numbers, to our misunderstood relationship to fairness, there are always ways to bend our counterpart’s reality so it conforms to what we ultimately want to give them, not to what they initially think they deserve.

Location: 1874

We’re always taught to look for the win-win solution, to accommodate, to be reasonable. So what’s the win-win here? What’s the compromise? The traditional negotiating logic that’s drilled into us from an early age, the kind that exalts compromises, says, “Let’s just split the difference and offer them $75,000. Then everyone’s happy.” No. Just, simply, no. The win-win mindset pushed by so many negotiation experts is usually ineffective and often disastrous. At best, it satisfies…

Location: 1879

Of course, as we’ve noted previously, you need to keep the cooperative, rapport-building, empathetic approach, the kind that creates a dynamic in which deals can be made. But you have to get rid of that naïveté. Because compromise—“splitting the difference”—can lead to terrible outcomes. Compromise is often a “bad deal” and a key theme we’ll hit in this chapter is that “no deal is better than a bad…

Location: 1884

To make my point on compromise, let me paint you an example: A woman wants her husband to wear black shoes with his suit. But her husband doesn’t want to; he prefers brown shoes. So what do they do? They compromise, they…

Location: 1888

one brown shoe. Is this the best outcome? No! In fact, that’s the worst possible outcome. Either of the two other outcomes—black or brown—would be better than the compromise. Next time you want to compromise, remind yourself of those mismatched shoes. So why are we so infatuated with the notion of compromise if it often leads to poor results? The real problem with compromise is that it has come to be known as this great concept, in…

Location: 1890

I’m here to call bullshit on compromise right now. We don’t compromise because it’s right; we compromise because it is easy and because it saves face. We compromise in order to say that at least we got half the pie. Distilled to its essence, we compromise to be safe. Most people in a negotiation are driven by…

Location: 1897

So don’t settle and—here’s a simple rule—never split the difference. Creative solutions are almost always preceded by some degree of risk, annoyance, confusion, and conflict. Accommodation and compromise produce none of that. You’ve got to embrace the hard stuff.…

Location: 1900

Time is one of the most crucial variables in any negotiation. The simple passing of time and its sharper cousin, the deadline, are the screw that pressures every deal to a conclusion. Whether your deadline is real and absolute or merely a line in the sand, it can trick you into believing that doing a deal now is more important than getting a good deal. Deadlines regularly make people say and do impulsive things that…

Location: 1904

Deadlines are often arbitrary, almost always flexible, and hardly ever trigger the consequences we think—or are told—they will. Deadlines are the bogeymen of negotiation, almost exclusively self-inflicted figments of our imagination, unnecessarily unsettling us for no good reason. The mantra we coach our clients on is, “No deal is better than a bad deal.”

Location: 1916

How close we were getting to their self-imposed deadline would be indicated by how specific the threats were that they issued. “Give us the money or your aunt is going to die” is an early stage threat, as the time isn’t specified. Increasing specificity on threats in any type of negotiations indicates getting closer to real consequences at a real specified time.

Location: 1929

Car dealers are prone to give you the best price near the end of the month, when their transactions are assessed. And corporate salespeople work on a quarterly basis and are most vulnerable as the quarter comes to a close.

Location: 1938

Now, knowing how negotiators use their counterpart’s deadlines to gain leverage would seem to suggest that it’s best to keep your own deadlines secret.

Location: 1940

Allow me to let you in on a little secret: Cohen, and the herd of negotiation “experts” who follow his lead, are wrong. Deadlines cut both ways. Cohen may well have been nervous about what his boss would say if he left Japan without an agreement. But it’s also true that Cohen’s counterparts wouldn’t have won if he’d left without a deal. That’s the key: When the negotiation is over for one side, it’s over for the other too.

Location: 1950

Business at the University of California, Berkeley, says that hiding a deadline actually puts the negotiator in the worst possible position. In his research, he’s found that hiding your deadlines dramatically increases the risk of an impasse. That’s because having a deadline pushes you to speed up your concessions, but the other side, thinking that it has time, will just hold out for more.

Location: 1954

In that sense, hiding a deadline means you’re negotiating with yourself, and you always lose when you do so.

Location: 1959

First, by revealing your cutoff you reduce the risk of impasse. And second, when an opponent knows your deadline, he’ll get to the real deal- and concession-making more quickly.

Location: 1960

NO SUCH THING AS FAIR In the third week of my negotiations class, we play my favorite type of game, that is, the kind that shows my students how much they don’t understand themselves (I know—I’m cruel). It’s called the Ultimatum Game, and it goes like this: After the students split into pairs of a “proposer” and an “accepter,” I give each proposer $10. The proposer then has to offer the accepter a round number of dollars. If the accepter agrees he or she receives what’s been offered and the proposer gets the rest. If the accepter refuses the offer, though, they both get nothing and the $10 goes back to me.

Location: 1964

Then I lay out how they’re wrong. First, how could they all be using reason if so many have made different offers? That’s the point: They didn’t. They assumed the other guy would reason just like them. “If you approach a negotiation thinking that the other guy thinks like you, you’re wrong,” I say. “That’s not empathy; that’s projection.”

Location: 1976

The most powerful word in negotiations is “Fair.” As human beings, we’re mightily swayed by how much we feel we have been respected. People comply with agreements if they feel they’ve been treated fairly and lash out if they don’t.

Location: 1990

Most people make an irrational choice to let the dollar slip through their fingers rather than to accept a derisory offer, because the negative emotional value of unfairness outweighs the positive rational value of the money. This irrational reaction to unfairness extends all the way to serious economic deals.

Location: 1997

In fact, of the three ways that people drop this F-bomb, only one is positive. The most common use is a judo-like defensive move that destabilizes the other side. This manipulation usually takes the form of something like, “We just want what’s fair.” Think back to the last time someone made this implicit accusation of unfairness to you, and I bet you’ll have to admit that it immediately triggered feelings of defensiveness and discomfort. These feelings are often subconscious and often lead to an irrational concession.

Location: 2020

The second use of the F-bomb is more nefarious. In this one, your counterpart will basically accuse you of being dense or dishonest by saying, “We’ve given you a fair offer.” It’s a terrible little jab meant to distract your attention and manipulate you into giving in. Whenever someone tries this on me, I think back to the last NFL lockout. Negotiations were getting down to the wire and the NFL Players Association (NFLPA) said that before they agreed to a final deal they wanted the owners to open their books. The owners’ answer? “We’ve given the players a fair offer.” Notice the horrible genius of this: instead of opening their books or declining to do so, the owners shifted the focus to the NFLPA’s supposed lack of understanding of fairness. If you find yourself in this situation, the best reaction is to simply mirror the “F” that has just been lobbed at you. “Fair?” you’d respond, pausing to let the word’s power do to them as it was intended to do to you. Follow that with a label: “It seems like you’re ready to provide the evidence that supports that,” which alludes to opening their books or otherwise handing over information that will either contradict their claim to fairness or give you more data to work with than you had previously. Right away, you declaw the attack.

Location: 2030

The last use of the F-word is my favorite because it’s positive and constructive. It sets the stage for honest and empathetic negotiation. Here’s how I use it: Early on in a negotiation, I say, “I want you to feel like you are being treated fairly at all times. So please stop me at any time if you feel I’m being unfair, and we’ll address it.” It’s simple and clear and sets me up as an honest dealer.

Location: 2041

If you can get the other party to reveal their problems, pain, and unmet objectives—if you can get at what people are really buying—then you can sell them a vision of their problem that leaves your proposal as the perfect solution.

Location: 2050

Know the emotional drivers and you can frame the benefits of any deal in language that will resonate.

Location: 2053

Or imagine that I offer you $20 to run a three-minute errand and get me a cup of coffee. You’re going to think to yourself that $20 for three minutes is $400 an hour. You’re going to be thrilled. What if then you find out that by getting you to run that errand I made a million dollars. You’d go from being ecstatic for making $400 an hour to being angry because you got ripped off. The value of the $20, just like the value of the coffee mug, didn’t change. But your perspective of it did. Just by how I position the $20, I can make you happy or disgusted by it.

Location: 2061

By far the best theory for describing the principles of our irrational decisions is something called Prospect Theory. Created in 1979 by the psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, prospect theory describes how people choose between options that involve risk, like in a negotiation. The theory argues that people are drawn to sure things over probabilities, even when the probability is a better choice. That’s called the Certainty Effect. And people will take greater risks to avoid losses than to achieve gains. That’s called Loss Aversion. That’s why people who statistically have no need for insurance buy it. Or consider this: a person who’s told he has a 95 percent chance of receiving $10,000 or a 100 percent chance of getting $9,499 will usually avoid risk and take the 100 percent certain safe choice, while the same person who’s told he has a 95 percent chance of losing $10,000 or a 100 percent chance of losing $9,499 will make the opposite choice, risking the bigger 95 percent option to avoid the loss. The chance for loss incites more risk than the possibility of an equal gain.

Location: 2068

To get real leverage, you have to persuade them that they have something concrete to lose if the deal falls through. 1. ANCHOR THEIR EMOTIONS

Location: 2079

To bend your counterpart’s reality, you have to start with the basics of empathy. So start out with an accusation audit acknowledging all of their fears. By anchoring their emotions in preparation for a loss, you inflame the other side’s loss aversion so that they’ll jump at the chance to avoid it. On my

Location: 2080

“I got a lousy proposition for you,” I said, and paused until each asked me to go on. “By the time we get off the phone, you’re going to think I’m a lousy businessman. You’re going to think I can’t budget or plan. You’re going to think Chris Voss is a big talker. His first big project ever out of the FBI, he screws it up completely. He doesn’t know how to run an operation. And he might even have lied to me.” And then, once I’d anchored their emotions in a minefield of low expectations, I played on their loss aversion. “Still, I wanted to bring this opportunity to you before I took it to someone else,” I said. Suddenly, their call wasn’t about being cut from $2,000 to $500 but how not to lose $500 to some other guy.

Location: 2088

2. LET THE OTHER GUY GO FIRST . . . MOST OF THE TIME.

Location: 2096

had a student named Jerry who royally screwed up his salary negotiation by going first (let me say that this happened before he was my student). In an interview at a New York financial firm, he demanded $110,000, in large part because it represented a 30 percent raise. It was only after he started that he realized that the firm had started everybody else in his program at $125,000. That’s why I suggest you let the other side anchor monetary negotiations.

Location: 2105

That’s not to say, “Never open.” Rules like that are easy to remember, but, like most simplistic approaches, they are not always good advice. If you’re dealing with a rookie counterpart, you might be tempted to be the shark and throw out an extreme anchor.

Location: 2120

3. ESTABLISH A RANGE While going first rarely helps, there is one way to seem to make an offer and bend their reality in the process. That is, by alluding to a range.

Location: 2125

this: When confronted with naming your terms or price, counter by recalling a similar deal which establishes your “ballpark,”

Location: 2127

In a recent study,4 Columbia Business School psychologists found that job applicants who named a range received significantly higher overall salaries than those who offered a number, especially if their range was a “bolstering range,” in which the low number in the range was what they actually wanted.

Location: 2133

They had to put something on the cover anyway, so it had zero cost to them and I gave them a steep discount on my fee. I constantly use that as an example in my negotiations now when I name a price. I want to stimulate my counterpart’s brainstorming to see what valuable nonmonetary gems they might have that are cheap to them but valuable to me. 5. WHEN YOU DO TALK NUMBERS, USE ODD ONES Every number has a psychological significance that goes beyond its value. And I’m not just talking about how you love 17 because you think it’s lucky. What I mean is that, in terms of negotiation, some numbers appear more immovable than others. The biggest thing to remember is that numbers that end in 0 inevitably feel like temporary placeholders, guesstimates that you can easily be negotiated off of. But anything you throw out that sounds less rounded—say, $37,263—feels like a figure that you came to as a result of thoughtful calculation. Such numbers feel serious and permanent to your counterpart, so use them to fortify your offers.

Location: 2146

6. SURPRISE WITH A GIFT You can get your counterpart into a mood of generosity by staking an extreme anchor and then, after their inevitable first rejection, offering them a wholly unrelated surprise gift.

Location: 2154

Unexpected conciliatory gestures like this are hugely effective because they introduce a dynamic called reciprocity; the other party feels the need to answer your generosity in kind. They will suddenly come up on their offer, or they’ll look to repay your kindness in the future. People feel obliged to repay debts of kindness.

Location: 2156

“How am I supposed to do that?” he asked in the next call.

Location: 2166

The kidnapper made another general threat against the aunt and again demanded the cash. That’s when I had the nephew subtly question the kidnapper’s fairness. “I’m sorry,” the nephew responded, “but how are we supposed to pay if you’re going to hurt her?”

Location: 2167

HOW TO NEGOTIATE A BETTER SALARY

Location: 2182

BE PLEASANTLY PERSISTENT ON NONSALARY TERMS

Location: 2186

an extra week of vacation

Location: 2190

SALARY TERMS WITHOUT SUCCESS TERMS IS RUSSIAN ROULETTE Once you’ve negotiated a salary, make sure to define success for your position—as well as metrics for your next raise. That’s meaningful for you and free for your boss,

Location: 2193

SPARK THEIR INTEREST IN YOUR SUCCESS AND GAIN AN UNOFFICIAL MENTOR Remember the idea of figuring what the other side is really buying? Well, when you are selling yourself to a manager, sell yourself as more than a body for a job; sell yourself, and your success, as a way they can validate their own intelligence and broadcast it to the rest of the company.

Location: 2197

Ask: “What does it take to be successful here?”

Location: 2201

“$134.5k—$143k.” In that one little move, Angel weaved together a bunch of the lessons from this chapter. The odd numbers gave them the weight of thoughtful calculation. The numbers were high too, which exploited his boss’s natural tendency to go directly to his price limit when faced by an extreme anchor. And they were a range, which made Angel seem less aggressive and the lower end more reasonable in comparison.

Location: 2221

filled ways. Using that knowledge is only, well, rational. As you work these tools into your daily life, remember the following powerful lessons: ■ All negotiations are defined by a network of subterranean desires and needs. Don’t let yourself be fooled by the surface. Once you know that the Haitian kidnappers just want party money, you will be miles better prepared. ■ Splitting the difference is wearing one black and one brown shoe, so don’t compromise. Meeting halfway often leads to bad deals for both sides. ■ Approaching deadlines entice people to rush the negotiating process and do impulsive things that are against their best interests.

Location: 2238

■ The F-word—“Fair”—is an emotional term people usually exploit to put the other side on the defensive and gain concessions. When your counterpart drops the F-bomb, don’t get suckered into a concession. Instead, ask them to explain how you’re mistreating them. ■ You can bend your counterpart’s reality by anchoring his starting point. Before you make an offer, emotionally anchor them by saying how bad it will be. When you get to numbers, set an extreme anchor to make your “real” offer seem reasonable, or use a range to seem less aggressive. The real value of anything depends on what vantage point you’re looking at it from. ■ People will take more risks to avoid a loss than to realize a gain. Make sure your counterpart sees that there is something to lose by inaction.

Location: 2246

Most important, we learned that successful negotiation involved getting your counterpart to do the work for you and suggest your solution himself. It involved giving him the illusion of control while you, in fact, were the one defining the conversation.

Location: 2274

The tool we developed is something I call the calibrated, or open-ended, question. What it does is remove aggression from conversations by acknowledging the other side openly, without resistance. In doing so, it lets you introduce ideas and requests without sounding pushy. It allows you to nudge.

Location: 2276

I’ll explain it in depth later on, but for now let me say that it’s really as simple as removing the hostility from the statement “You can’t leave” and turning it into a question. “What do you hope to achieve by going?”

Location: 2278

And all negotiation, done well, should be an information-gathering process that vests your counterpart in an outcome that serves you.

Location: 2368

That’s when I had my “Holy shit!” moment and realized that this is the technique I’d been waiting for. Instead of asking some closed-ended question with a single correct answer, he’d asked an open-ended, yet calibrated one that forced the other guy to pause and actually think about how to solve the problem.

Location: 2389

It’s a “how” question, and “how” engages because “how” asks for help.

Location: 2392

Best of all, he doesn’t owe the kidnapper a damn thing. The guy volunteers to put the girlfriend on the phone: he thinks it’s his idea. The guy who just offered to put the girlfriend on the line thinks he’s in control. And the secret to gaining the upper hand in a negotiation is giving the other side the illusion of control.

Location: 2393

The genius of this technique is really well explained by something that the psychologist Kevin Dutton says in his book Split-Second Persuasion.1 He talks about what he calls “unbelief,” which is active resistance to what the other side is saying, complete rejection. That’s where the two parties in a negotiation usually start.

Location: 2395

If you don’t ever get off that dynamic, you end up having showdowns, as each side tries to impose its point of view. You get two hard skulls banging against each other, like in Dos Palmas. But if you can get the other side to drop their unbelief, you can slowly work them to your point of view on the back of their energy, just like the drug dealer’s question got the kidnapper to volunteer to do what the drug dealer wanted.

Location: 2398

Our job as persuaders is easier than we think. It’s not to get others believing what we say. It’s just to stop them unbelieving. Once we achieve that, the game’s half-won. “Unbelief is the friction that keeps persuasion in check,” Dutton says. “Without it, there’d be no limits.”

Location: 2403

What’s so powerful about the senior doctor’s technique is that he took what was a showdown—“I’m going to leave” versus “You can’t leave”—and asked questions that led the patient to solve his own problem . . . in the way the doctor wanted. It was still a kind of showdown, of course, but the doctor took the confrontation and bravado out of it by giving the patient the illusion of control.

Location: 2413

you can just say the price is a bit more than you budgeted and ask for help with one of the greatest-of-all-time calibrated questions: “How am I supposed to do that?” The critical part of this approach is that you really are asking for help and your delivery must convey that.

Location: 2420

My advice for her was simple: I told her to engage them in a conversation where she summarized the situation and then asked, “How am I supposed to do that?”

Location: 2429

Now, think about how my client’s question worked: without accusing them of anything, it pushed the big company to understand her problem and offer the solution she wanted. That in a nutshell is the whole point of open-ended questions that are calibrated for a specific effect.

Location: 2440

Like the softening words and phrases “perhaps,” “maybe,” “I think,” and “it seems,” the calibrated open-ended question takes the aggression out of a confrontational statement or close-ended request that might otherwise anger your counterpart. What makes them work is that they are subject to interpretation by your counterpart instead of being rigidly defined. They allow you to introduce ideas and requests without sounding overbearing or pushy. And that’s the difference between “You’re screwing me out of money, and it has to stop” and “How am I supposed to do that?”

Location: 2442

But calibrated questions are not just random requests for comment. They have a direction: once you figure out where you want a conversation to go, you have to design the questions that will ease the conversation in that direction while…

Location: 2449

First off, calibrated questions avoid verbs or words like “can,” “is,” “are,” “do,” or “does.” These are closed-ended questions that can be answered with a simple “yes” or a “no.” Instead, they start with a list of words people know as reporter’s questions: “who,” “what,” “when,” “where,” “why,” and “…

Location: 2453

But let me cut the list even further: it’s best to start with “what,” “how,” and sometimes “why.” Nothing else. “Who,” “when,” and “where” will often just get your counterpart to share a fact without thinking. And “why” can backfire. Regardless of what language the word “why” is translated into,…

Location: 2457

The only time you can use “why” successfully is when the defensiveness that is created supports the change you are trying to get them to see. “Why would you ever change from the way you’ve always done things and try my approach?” is an example. “Why would your company ever change from your long-standing vendor and choose our…

Location: 2460

don’t touch it. Having just two words to start with might not seem like a lot of ammunition, but trust me, you can use “what” and “how” to calibrate nearly any question. “Does this look like something you would like?” can become “How does this look to you?” or “What about this works for you?” You can even ask, “What about this doesn’t work for…

Location: 2463

You should use calibrated questions early and often, and there are a few that you will find that you will use in the beginning of nearly every negotiation. “What is the biggest challenge you face?” is one of those questions. It just gets the other side to teach you something about themselves, which is critical to any negotiation because all negotiation is an information-gathering process. Here are some other great standbys that I use in almost every negotiation, depending on the situation: ■ What about this is important to you? ■ How can I help to make this better for us? ■ How would you like me to proceed? ■ What is it that brought us into this situation? ■ How can we solve this problem? ■ What’s the objective? / What are we trying to accomplish here? ■ How am I supposed to do that? The implication of any well-designed calibrated question is that you want what the other guy wants but you need his intelligence to overcome the problem. This really appeals to very aggressive or egotistical counterparts. You’ve not only implicitly asked for help—triggering goodwill and less defensiveness—but you’ve engineered a…

Location: 2468

Let’s pause for a minute here, because there’s one vitally important thing you have to remember when you enter a negotiation armed with your list of calibrated questions. That is, all of this is great, but there’s a rub: without self-control and emotional regulation, it doesn’t work. The very first thing I talk about when I’m training new negotiators is the critical importance of self-control. If you can’t control your own emotions, how can you expect to influence the emotions of another party?

Location: 2501

The script we came up with hit all the best practices of negotiation we’ve talked about so far. Here it is by steps: 1. A “No”-oriented email question to reinitiate contact: “Have you given up on settling this amicably?”

Location: 2514

2. A statement that leaves only the answer of “That’s right” to form a dynamic of agreement: “It seems that you feel my bill is not justified.” 3. Calibrated questions about the problem to get him to reveal his thinking: “How does this bill violate our agreement?” 4. More “No”-oriented questions to remove unspoken barriers: “Are you saying I misled you?” “Are you saying I didn’t do as you asked?” “Are you saying I reneged on our agreement?” or “Are you saying I failed you?” 5. Labeling and mirroring the essence of his answers if they are not acceptable so he has to consider them again: “It seems like you feel my work was subpar.” Or “. . . my work was subpar?” 6. A calibrated question in reply to any offer other than full payment, in order to get him to offer a solution: “How am I supposed to accept that?” 7. If none of this gets an offer of full payment, a label that flatters his sense of control and power: “It seems like you are the type of person who prides himself on the way he does business—rightfully so—and has a knack for not only expanding the pie but making the ship run more efficiently.” 8. A long pause and then one more “No”-oriented question: “Do you want to be known as someone who doesn’t fulfill agreements?”

Location: 2517

Even with all the best techniques and strategy, you need to regulate your emotions if you want to have any hope of coming out on top.

Location: 2538

But you have to keep away from knee-jerk, passionate reactions. Pause. Think. Let the passion dissipate. That allows you to collect your thoughts and be more circumspect in what you say. It also lowers your chance of saying more than you want to.

Location: 2540

Who has control in a conversation, the guy listening or the guy talking? The listener, of course. That’s because the talker is revealing information while the listener, if he’s trained well, is directing the conversation toward his own goals. He’s harnessing the talker’s energy for his own ends. When you try to work the skills from this chapter into your daily life, remember that these are listener’s tools. They are not about strong-arming your opponent into submission. Rather, they’re about using the counterpart’s power to get to your objective. They’re listener’s judo.

Location: 2557

Don’t try to force your opponent to admit that you are right. Aggressive confrontation is the enemy of constructive negotiation. ■ Avoid questions that can be answered with “Yes” or tiny pieces of information. These require little thought and inspire the human need for reciprocity; you will be expected to give something back. ■ Ask calibrated questions that start with the words “How” or “What.” By implicitly asking the other party for help, these questions will give your counterpart an illusion of control and will inspire them to speak at length, revealing important information. ■ Don’t ask questions that start with “Why” unless you want your counterpart to defend a goal that serves you. “Why” is always an accusation, in any language. ■ Calibrate your questions to point your counterpart toward solving your problem. This will encourage them to expend their energy on devising a solution. ■ Bite your tongue. When you’re attacked in a negotiation, pause and avoid angry emotional reactions. Instead, ask your counterpart a calibrated question. ■ There is always a team on the other side. If you are not influencing those behind the table, you are vulnerable.

Location: 2563

Calibrated “How” questions are a surefire way to keep negotiations going. They put the pressure on your counterpart to come up with answers, and to contemplate your problems when making their demands.

Location: 2656

With enough of the right “How” questions you can read and shape the negotiating environment in such a way that you’ll eventually get to the answer you want to hear. You just have to have an idea of where you want the conversation to go when you’re devising your questions. The trick to “How” questions is that, correctly used, they are gentle and graceful ways to say “No” and guide your counterpart to develop a better solution—your solution. A gentle How/No invites collaboration and leaves your counterpart with a feeling of having been treated with respect.

Location: 2658

As Julie did, the first and most common “No” question you’ll use is some version of “How am I supposed to do that?” (for example, “How can we raise that much?”). Your tone of voice is critical as this phrase can be delivered as either an accusation or a request for assistance. So pay attention to your voice.

Location: 2664

This question tends to have the positive effect of making the other side take a good look at your situation. This positive dynamic is what I refer to as “forced empathy,” and it’s especially effective if leading up to it you’ve already been empathic with your counterpart. This engages the dynamic of reciprocity to lead them to do something for you. Starting with José’s kidnapping, “How am I supposed to do that?” became our primary response to a kidnapper demanding a ransom. And we never had it backfire.

Location: 2667

Besides saying “No,” the other key benefit of asking “How?” is, quite literally, that it forces your counterpart to consider and explain how a deal will be implemented. A deal is nothing without good implementation. Poor implementation is the cancer that eats your profits. By making your counterparts articulate implementation in their own words, your carefully calibrated “How” questions will convince them that the final solution is their idea. And that’s crucial. People always make more effort to implement a solution when they think it’s theirs. That is simply human nature. That’s why negotiation is often called “the art of letting someone else have your way.” There are two key questions you can ask to push your counterparts to think they are defining success their way: “How will we know we’re on track?” and “How will we address things if we find we’re off track?” When they answer, you summarize their answers until you get a “That’s right.” Then you’ll know they’ve bought in.

Location: 2680

As I’ve noted, when they say, “You’re right,” it’s often a good indicator they are not vested in what is being discussed. And when you push for implementation and they say, “I’ll try,” you should get a sinking feeling in your stomach. Because this really means, “I plan to fail.”

Location: 2689

When you hear either of these, dive back in with calibrated “How” questions until they define the terms of successful implementation in their own voice. Follow up by summarizing what they have said to get a “That’s right.”

Location: 2691

It turns out that the head of the division that needed the training killed the deal. Maybe this guy felt threatened, slighted, or otherwise somehow personally injured by the notion that he and his people “needed” any training at all. (A surprisingly high percentage of negotiations hinge on something outside dollars and cents, often having more to do with self-esteem, status, and other nonfinancial needs.) We’ll never know now.

Location: 2729